Strategic Dynamics and Market Impacts of Share Buybacks in India

Understanding the Core: What is a Share Buyback?

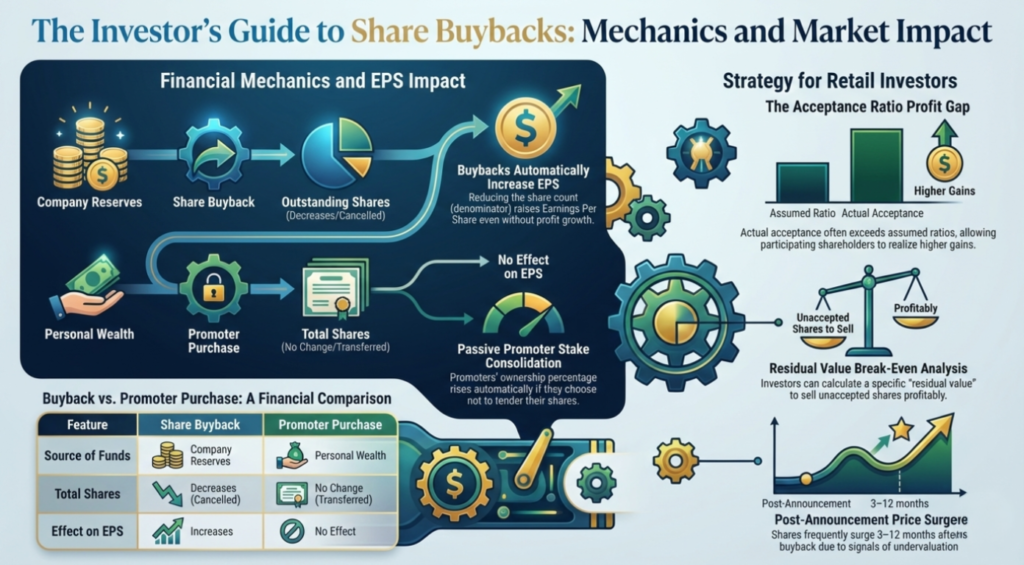

A share buyback occurs when a listed company utilizes its own cash reserves to purchase its outstanding shares from the market, subsequently extinguishing them (Cancelling/ destroying them electronically). It might seem like a corporate paradox: why would a profitable corporation spend billions of its own cash just to make its shares disappear? From a capital allocation perspective, this is a sophisticated puzzle. Share buybacks have emerged as a sophisticated financial tool for Indian listed companies to optimize capital structure, reward shareholders, and signal market confidence.

Strategic Distinctions: Buybacks vs. Promoter Purchases

Understanding the difference between Buybacks vs. Promoter Purchases is vital

It is a common retail misconception that a “buyback” is synonymous with “promoters buying shares.There is a significant legal and financial difference between a company repurchasing its own shares and promoters buying shares individually.

Comparative Analysis

FEAUTURE | SHARE BUYBACK | PROMOTER PURCHASE |

Purchasing Entity | The Company | The Promoters (Individuals/Entities) |

Source of Funds | Company Profits/Reserves (Balance Sheet) | Personal Wealth of Promoters |

Total Shares | Decreases (Shares are usually extinguished) | No Change (Shares simply change hands) |

Effect on EPS | Increases due to reduced denominator | No effect |

Promoter % | Increases (ownership of a “smaller pie”) | Increases (ownership of more units) |

Motives for Buybacks

- Signaling Confidence: Announcements often signal to the market that the company believes its shares are undervalued.By offering to repurchase shares at a significant premium, a company issues a potent signal of Undervaluation. This communicates management’s confidence in the intrinsic value of the business, often acting as a catalyst for price correction.

- Capital Structure Optimization: Efficiently utilizing surplus cash when growth opportunities are limited. Boards utilize surplus cash to retire equity, thereby improving Return on Equity (ROE) and achieving a leaner, more efficient capital base without the procedural delays of court-approved capital reductions.

- Defense Mechanism: Buybacks are increasingly leveraged for Promoter Holding Consolidation. By shrinking the equity base while promoters retain their units, the firm strengthens internal control and constructs a robust barrier against hostile takeover attempts.

- Tax Efficiency: Historically, buybacks have been preferred over dividends due to more favorable tax implications for promoters and large shareholders.

The popularity of buybacks in India surged following the 2016 Budget. At that time, dividends exceeding ₹10 Lakhs became subject to a “double taxation” scenario: the company paid Dividend Distribution Tax (DDT), and the individual paid additional income tax. Buybacks became the preferred vehicle for returning value to shareholders because they were more tax-efficient.

To Make Profits Look Better Without Earning More:The primary mechanical impact of a buyback is the immediate improvement of Earnings Per Share (EPS). EPS is calculated by dividing total net income (minus preferred dividends) by the weighted average number of common shares outstanding.When a company repurchases and extinguishes its shares, the denominator decreases. Even if net income remains stagnant, the EPS rises because the same “profit pie” is divided among fewer owners.

This can be best explained by Pizza Analogy Imagine a pizza with 8 slices shared by 4 people; each person gets 2 slices. In a buyback like situation, one person leaves and his 2 slices are removed from the table and discarded. Now, only 6 slices remain for the 3 remaining people. Each person’s “% share” of the pizza has increased, even though they still have the same 2 of pieces as no new pizza was baked.

The Life-cycle of a Buyback: A Step-by-Step Timeline

Participating in a corporate action requires strict adherence to chronological milestones:

- Announcement: The board meets to declare intent, the offer price (usually at a premium), and the total size.

- Record Date: This is the cut-off point used to categorize shareholders. Critically, it determines if you qualify as a “Retail/Small Investor” (holding shares worth less than ₹2 Lakhs).

- Tender Period: The window where you officially offer your shares to the company.

- Verification & Acceptance: The Registrar (RTA) checks eligibility and calculates the final acceptance.

- Settlement: Funds are credited directly to your bank account.

To be eligible, shares must be in your demat account by the Record Date. Because the Indian market operates on a T+2 settlement cycle, you must purchase the stock at least 2 trading days prior to the record date to ensure you are officially on the books.

Once your eligibility is confirmed, the execution of the trade falls to the investor’s manual input.

Tendering Your Shares: The Role of Brokers and RTAs

Participation is never automatic. You must actively “tender” your shares through your broker’s online portal. The tender form typically highlights three fields:

- Shares held on record date: Pre-filled based on your holdings.

- Shares entitled for buyback: The minimum amount the company is legally obligated to take.

- Shares offered for buyback: The number you wish to sell.

Strategist’s Pro-Tip: Always tender your full eligibility—and perhaps more—if you wish to maximize your exit. While “Entitled” shares are guaranteed, the company can and often does accept more if other shareholders fail to participate. Remember: Not filling the form means you are not participating, regardless of your eligibility.

The Broker provides the platform, the RTA verifies the shares, and the cash is eventually credited directly to your bank account, not your brokerage trading limit. However, the quantity the company actually buys depends on a shifting metric.

What is in it for a Retail Investor

The Indian regulatory framework, governed by SEBI, specific structural advantages for small shareholders (holding not exceeding a valuation of more than ₹2 Lakh on the Record Date), creates a protected arbitrage window. SEBI mandates a 15% reservation for these small shareholders in every buyback offer. This reservation ensures a dedicated liquidity pool for retail participants. This environment allows retail participants to capture premiums that are structurally unavailable to institutional or high-net-worth players.

For the retail investor the single most important execution metrics is the Acceptance Ratio (AR). The Acceptance Ratio (AR), denotes the proportion of the tendered shares that the company intends to repurchase.

The SEBI mandate ensures that the “retail bucket” often enjoys a significantly higher AR than the general category.

Analysis of 76 Indian companies indicates that the Actual Acceptance Ratio (calculated after the completion of buyback) is frequently higher than the Assumed Acceptance Ratio (calculated at the announcement date). This discrepancy creates a tactical “alpha” for participating shareholders, driven largely by the non-participation of large institutional holders or promoters, which leaves a larger portion of the reserved retail pool available for those who do tender.

To mitigate the risk of shares remaining unaccepted, investors should utilize the Residual Value formula to determine the break-even point:

Residual Value = (Initial Investment – Buyback Profit) / Residual Shares

Let’s understand the whole process with the Case Study of share buybacks by the company TIPS in the year 2020:

To qualify for the SEBI “Small share holder category” and to maximize profits a retail investor would typically have a holding just less than the ₹2 Lakh limit on the record date. At the time of buyback announcement, price of TIPS shares where ₹11. Let’s assume Initial Investment was ₹1,99,991 (18,181 shares at ₹11).

As per Announcement assumed acceptance ratio (AR) was 1.41% and Buy Back Premium was ₹140

- No. of shares to be bought: 257 {18181*1.41/100}

- Buyback Profit: ₹33,168. {257*(140-11)}

- Residual Shares: 17,924 {18,181 – 257)}

- Break-Even Point: ₹9.15. {(Initial Investment ₹1,99,991 – Profit ₹33,168) / 17,924 Residual shares.}

This structural advantage is compounded by a “Tax Arbitrage Layer.” Under the Union Budget 2026 framework, a stark differential exists in the tax treatment of buyback gains:

- Retail Investors: Subject to a favorable tax regime, typically 12.5% for long-term gains.

- Promoters/Corporates: Effective rates reach 22% for domestic companies and up to 30% for individual or foreign promoters.

THE GAME PLAN

- Respect the T+2 Clock: If you don’t own the shares two trading days before the Record Date, you aren’t eligible for the retail reservation.

- The Math Favors the Bold: Actual Acceptance is almost always higher than Assumed Acceptance because large players often stay out. Don’t let a low initial estimate deter you. Also ensure that entire holding is tendered for buyback.

- Execute with a Target: Use the Residual Value formula before the tender period ends. This allows you to set automated limit orders for your remaining shares, securing your profit the moment they return to your demat account.

Market Performance Analysis and Empirical Findings

Post-buyback price performance serves as the ultimate validation of capital allocation decisions. Based on the International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT) empirical findings, the impact varies significantly by market capitalization:

- Large Cap Stocks: These generally demonstrate a “steady increase” in valuation post-buyback (e.g., TCS 2020-21), signaling that the market views the action as a validation of steady growth. However, some mature entities like NTPC and GAIL maintained constant pricing, suggesting the market had already priced in the capital return.

- Mid Cap Stocks: Showed robust performance in growth-oriented cases like Ajanta Pharma, while maintenance of value (constant performance) was observed in companies like Aster DM and KIOCL.

- Small Cap Stocks: This segment presents the highest risk. Significant price decreases were observed in several entities, such as Aarti Drugs and Nucleus Software, following the buyback completion. While exceptions like Savita Oil Technologies saw temporary surges, they were often followed by valuation dips.

Analysis indicates that the optimal timeframe for price surges is between 3 months and 1 year post-announcement, correlating with the market’s realization of undervaluation.

StrategicTakeaways for Decision Makers

- For Large Cap Entities: Treat buybacks as a validation of financial maturity and steady growth; the signaling power is highest when coupled with consistent earnings growth.

- For Small Cap Entities: Exercise caution. Buybacks in this segment are often defensive maneuvers during periods of valuation erosion. Without strong fundamentals, the “signal” may fail to prevent further price declines.

- Execution Alpha: Note that actual acceptance ratios historically exceed assumed ratios due to the non-participation of large-block holders. This provides a predictable tactical advantage for retail participants.

- The Signaling Paradox: In mature sectors like IT services, management must clearly articulate whether a buyback is a value-correction tool or a response to a lack of internal growth opportunities to avoid negative sentiment.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Acceptance Ratio: The ratio of shares a company actually buys back to the total number of shares tendered by investors.

- Basic EPS: Profit available to common shareholders divided by the weighted average of currently outstanding shares.

- Free Float: The portion of a company’s outstanding shares that are available for trading by the general public, excluding promoter holdings.

- Open Market Buyback: A method where a company repurchases its shares directly from the stock exchange over time.

- Promoter: The individuals or entities who consolidate control and management of a company.

- Record Date: The specific date set by a company to identify which shareholders are eligible to participate in a buyback offer.

- Residual Value: The break-even sell price for shares remaining in an investor’s portfolio after a partial buyback acceptance.

- Tender Offer: A public offer by a company to buy back a specific number of shares at a fixed price, usually at a premium.

- Weighted Average Shares: The calculated average of shares outstanding throughout a period, used to account for fluctuations in share count.